With the fourth largest population in the world, one might expect Indonesia to be one of the strongest economies. However, it currently lies at just 16th on the share of world Gross Domestic Product (GDP, Worldometer). The middle-income country was under Dutch rule for 350 years, experienced strict political revolution and reform, and faced serious troubles during the Asian financial crisis in 1997, but it has since seen consistent growth. Attempting to boost its economy, Indonesia has begun to explore the untapped potential lying beneath its land, particularly in the growing mining and processing industries. President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, seeking to break free from the shackles of a colonial past, has turned to nickel as a key resource, riding the wave of the electric vehicle era and increased environmental consciousness among consumers and corporations alike.

In a strategic move, President Jokowi imposed a ban on raw nickel exports in January 2020 to develop a downstream process for Indonesia’s valued natural resource. This policy shift aimed to maximize profits by requiring the ore to be domestically processed into more final products. Such a process ensures that Indonesia not only supplies the raw material but also participates in the value addition chain, creating more jobs and generating higher revenues from selling refined nickel products. However, this bold move has not been without its challenges. Indonesia’s possession of about 52 percent of the world’s total nickel reserves has caused the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization to raise concerns, citing the European Union’s demand for the raw ore in its stainless steel industry. President Jokowi defends his export policies, emphasizing the importance of the downstream industry for Indonesia’s economy. Such demands from the IMF and WTO can even be seen as tainted with a colonial desire for cheap natural resources from countries with less international influence and power.

Indonesia has seen great growth from this new processing structure with the Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP) at the heart of its nickel boom. Established in 2013 in Sulawesi’s Morowali regency, the complex features several smelters with its main products being nickel, stainless steel, and carbon steel. IMIP is majority-owned by Tsingshan Holding Group, one of the largest private Chinese stainless steel manufacturing companies, with the Indonesian Bintang Delapan Group also holding a smaller share. At first glance, this large foreign investment might look as if most of Indonesia’s natural resource profits are flowing out of the country, but Investment Minister Bahlil Lahadalia claims that these foreign corporations are the few willing and able to offer the funding for such expensive projects and that the profits go back to Indonesia, meaning both groups benefit.

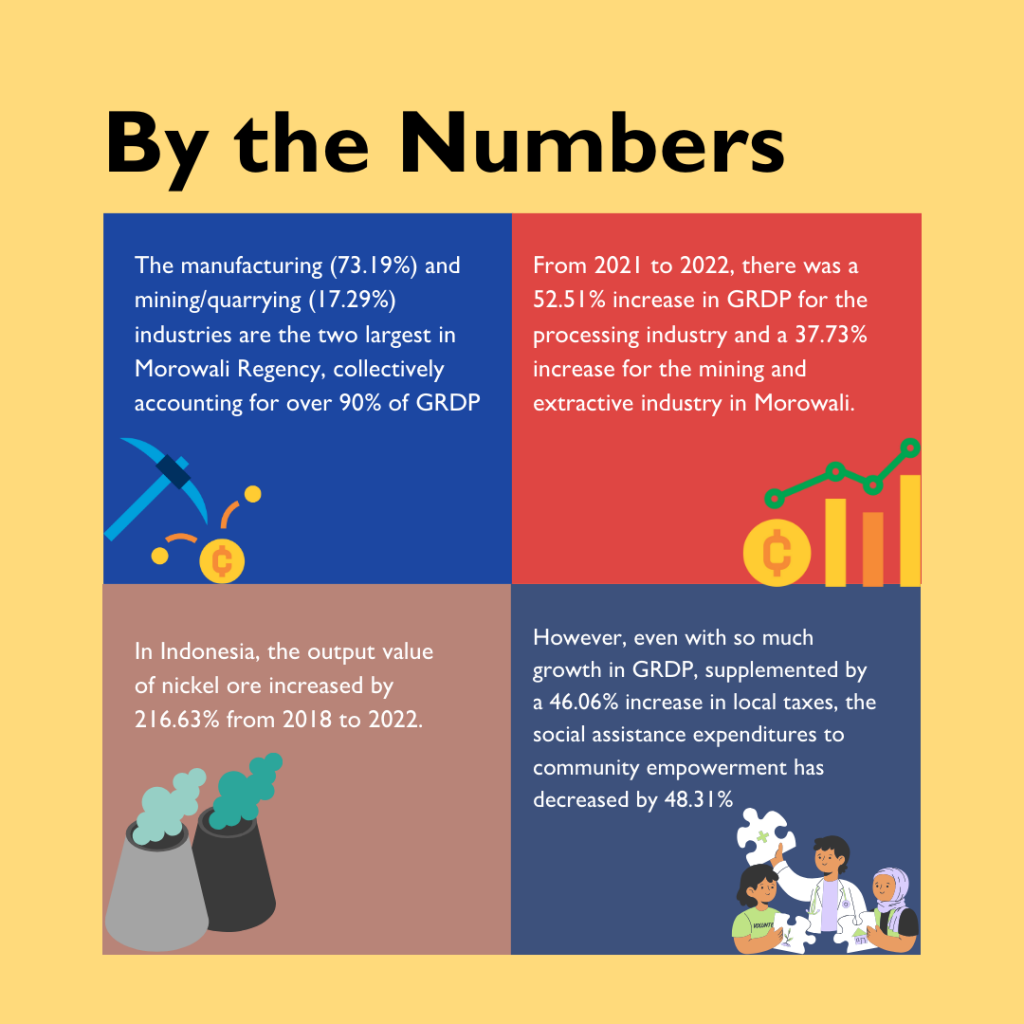

In Morowali specifically, there was a 52.1 percent increase in Gross Regional Domestic Product (GRDP) for the processing industry and a 37.73 percent increase for the mining and extractive industry from 2021 to 2022. These fields are the two largest contributors to GRDP, accounting for over 90 percent of the value and demonstrating the regency’s strong reliance on them (BPS Morowali). However, even with so much growth in GRDP, supplemented by a 46.06 percent increase in local taxes, the social assistance expenditures to Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) has decreased by 48.31 percent. Generally, NGOs are established to promote social welfare and alleviate local problems, so a decrease in funding to these groups might limit their reach. This is especially notable when the remaining budget surplus (SILPA) saw an increase of 78.51 percent (LKPD Kabupaten Morowali).

Moreover, the demand for nickel has given rise to several instances of land grabbing, such as the Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP) in Halmahera, North Maluku. This large nickel mine, which is also partly owned by the Tsingshan Group, faces opposition from the O Hongana Manyawa, one of Indonesia’s last nomadic indigenous peoples, whose traditional lands are threatened by the mining park. Not only is the land stripped from the hands of locals through intimidation and other unethical methods, but it is further destroyed by the mining operations that cut down the forests to reach the nickel beneath the soil. These actions have made it more difficult for the group to gather food, have destroyed the environment, and threaten the local population’s future generations.

Additionally, the monetary allure of the mining industry has attracted other criminal elements, perpetuating corruption. Government officials, enticed by the promise of wealth, have been implicated and named suspects in several illegal mining scandals, such as former director-general of the Ministry of Mining and Coal Ridwan Djamaluddin who was arrested for allegedly allowing miners to operate outside of their approved areas. Djamaluddin’s actions resulted in the loss of IDR 5.7 trillion of revenue for the government from that nickel. This not only tarnishes the industry’s reputation but also raises questions about the government’s involvement in the field. According to MAKI, the Indonesia Corruption Watch, there is currently over IDR 3.7 trillion (over USD 238.817 million) circulating in the economy from illegal mining operations, demonstrating the extent to which this problem has risen. Efforts have been made to crack down on this. However, refusing to accept illegally mined nickel has caused the smelter in Morowali to import raw nickel ore from the Philippines to fulfill their supply needs. Transporting raw nickel is not cheap and this just further increases Indonesia’s dependence on foreign countries, counteracting President Jokowi’s attempts at downstreaming. Indonesia still has a lot of work for its anti-corruption programs and must discover how to balance this dilemma.

The gender disparity also adds another layer to this complex tapestry of challenges. Despite contributing 55.71 percent to the population, women constitute only 30 percent of the workforce in Morowali. While it is important to acknowledge that 37 percent of the women are economically active compared to 84 percent of men in the regency, female representation is still lacking in the extractive industries (BPS Morowali). Addressing these differences is crucial for ensuring that the benefits of the nickel industry are shared more inclusively.

Various steps have already been taken to mitigate these issues, but there is still much more work to be done in the mining and extractive industries by corporations and governments alike. First, participants must be held to a greater standard of transparency to prevent corruption and illegal mining. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative plays a vital role in promoting this by providing open data sources for the public which can also be used by policymakers when drafting laws to govern this sector. Publish What You Pay (PWYP) is also doing great work as a NGO Coalition dealing with the governance of the mineral and coal sector. PWYP is actively engaged in regulating and advising the mining industry, advocating for responsible practices and equitable distribution of profits.

As Indonesia navigates the complexities of its nickel industry, it faces the delicate task of balancing economic growth with environmental sustainability, social equity, and transparency. The nation has a bountiful supply of natural resources that it must manage in a profitable and conscious way. Indonesia’s journey into the world of nickel mining reflects the broader challenges and opportunities that emerging economies face as they seek to capitalize on their natural resources.

Written by: Remzy Abacy, Student Intern at IDEA from Princeton University, United States